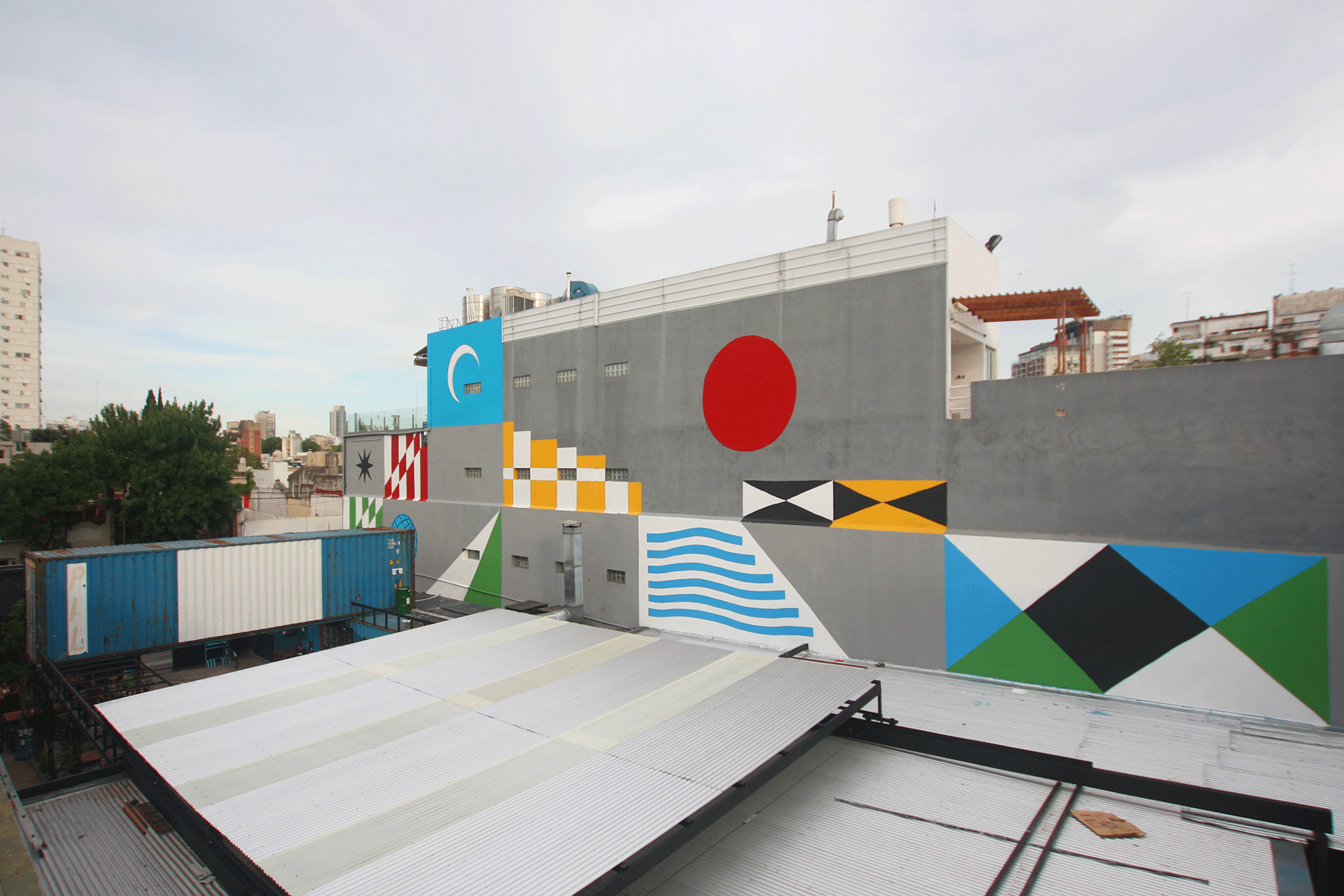

Buenos Aires, Argentina 🇦🇷

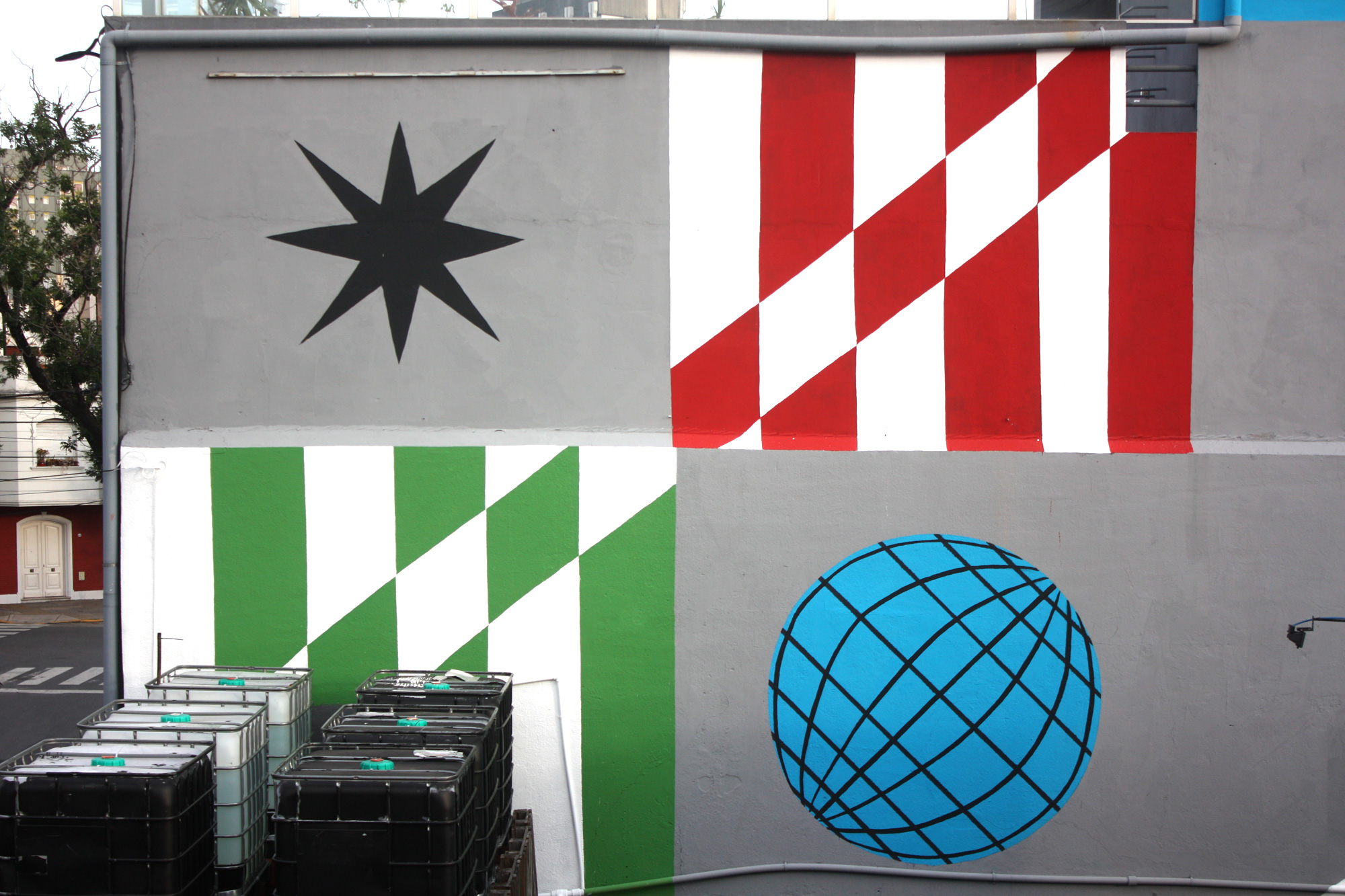

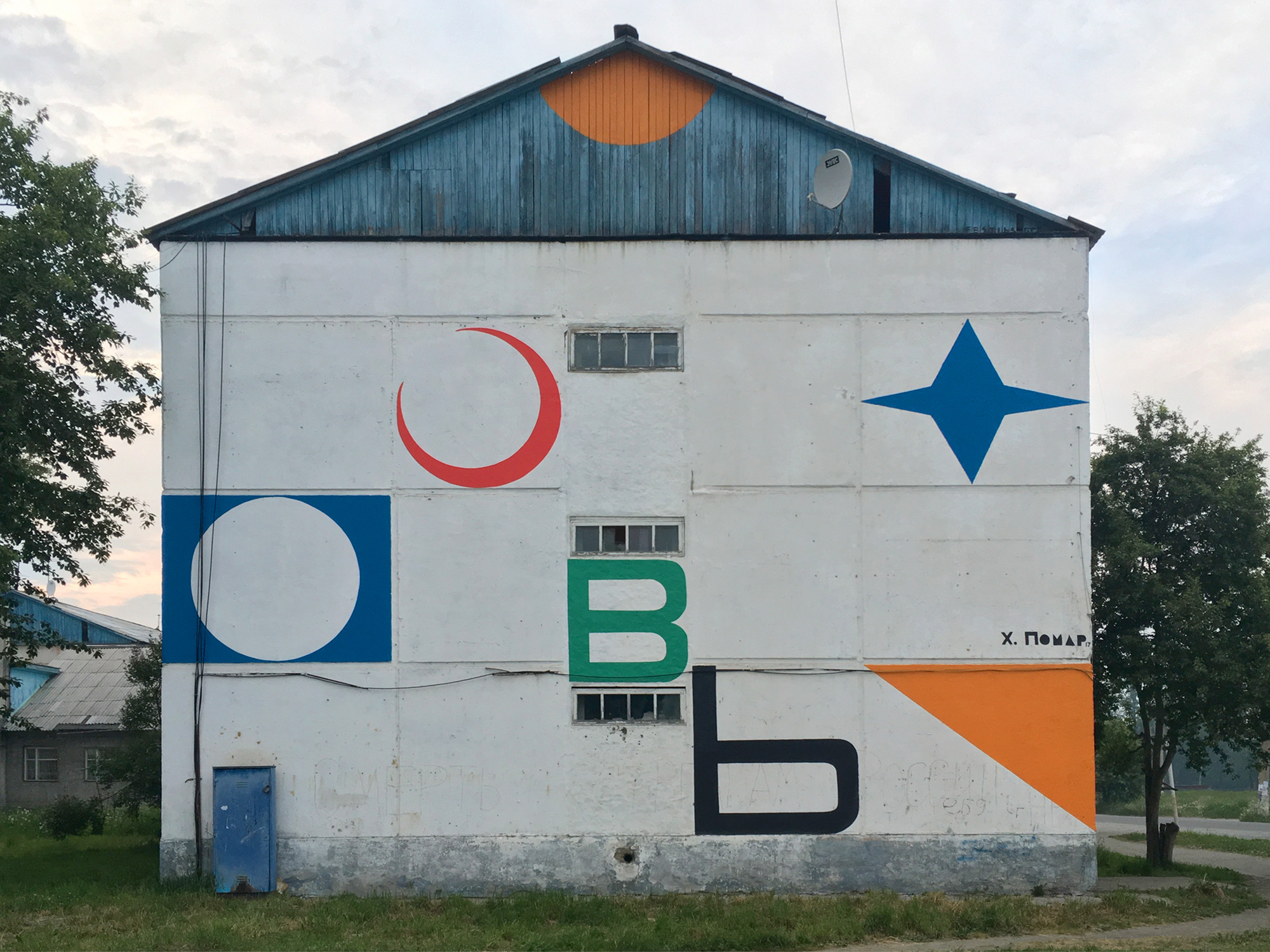

Serie “Herencia de Buenos Aires”

Proyecto independiente y autogestionado

Pintura acrílica sobre muro de concreto

2 x 31 m

2018

Drone de Unlimited.fly y Aerovisuales

Video dirigido por Orco Videos y Juan Ignacio Zevallos

Diseño web de Los Caballos: 64tonosdebuenosaires.com.ar

•

Durante varios meses conversé con amigxs, taxistas, mozxs, transeúntes y anónimxs sobre una pregunta que me atrapó: ¿cuál es la canción que representa a Buenos Aires? De Piazzolla a Sumo, de la Tana Rinaldi a DJs Pareja, pasando por Ca7riel y Soda Stereo, empecé a juntar respuestas en una lista de Spotify que llamé "64 tonos de Buenos Aires". Una noche salí a caminar por... Leer más